Carnasserie Rock Art Excavation 2023

Why excavate rock art?

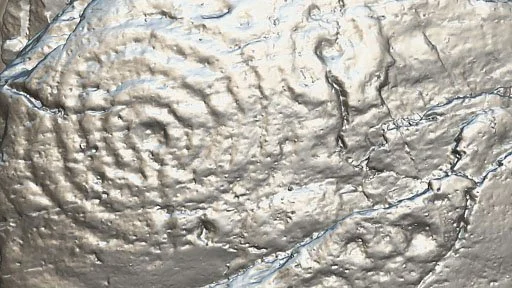

During the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, people created thousands of carvings on rocky outcrops throughout Kilmartin Glen. Most of these carvings consist of dots, circles, and lines, commonly known as cup and ring markings. They range from simple clusters of cup marks (circular hollows) to complex designs. Some of Scotland's largest and most elaborate rock art panels are found here.

Rock art in the Kilmartin area is part of a wider phenomenon, and similar carvings are found throughout Scotland, northern England, Wales, and Ireland. But why did people put so much effort into creating these symbols? Exactly how old are they, and what was their significance? These questions have been asked ever since rock art was first recognised over a century ago, and hundreds of explanations have been suggested.

Until recent years, there has been a tendency for cup and ring markings to be studied, quite literally, as symbols set in stone. Emphasis was placed on recording and illustrating the markings themselves, rather than examining their wider context or even how they were made. While this has led to a valuable visual record, it has sometimes resulted in the carvings being viewed in isolation from their wider context, the surrounding landscape. This kind of rock art has also proven to be notoriously difficult to date. Fortunately, new approaches to fieldwork and recording are now transforming our understanding.

Between 2004 and 2009, excavations at Torbhlaren in nearby Kilmichael Glen (conducted by the University of Southampton) and Ormaig (in collaboration with Kilmartin Museum/University of Southampton) revealed remarkable insights into the creation and use of rock art.

Above: Excavations in progress at Torbhlaren in 2007 (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Above: Excavations at Ormaig in 2007 (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Both sites revealed hammerstones that prehistoric people used to carve the rocks. At Torbhlaren, thousands of pieces of broken quartz and modest quantities of worked flint and Arran pitchstone were also discovered. These findings significantly changed our understanding, since they highlighted the methods used to create rock art. They serve as a crucial reminder that the symbols we see on the rocks were produced through deliberate and sustained actions, resulting in dust and percussive sounds. The use of quartz is particularly interesting because this material has unique physical properties. Its semi-translucent crystals sparkle when they catch the light and produce an eerie glow when struck together in the dark.

Above: A fractured quartz hammerstone found at Torbhlaren (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Above: Fractured quartz discovered at Torbhlaren (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Rock art is incredibly difficult to date. Torbhlaren is one of the few rock art sites in the landscape to have produced radiocarbon dates which suggest the cup and ring markings were made there through the Later Neolithic and the Bronze Age (c.3000 to 1200 BC).

Excavations elsewhere in Scotland and northern England have also added fresh, and often unexpected, insights into rock art. But many questions remain! Given the abundance of rock in the Kilmartin area and its proximity to other kinds of monuments, further investigations are essential. The Regional Research Framework for Argyll has identified rock art as a key subject for research:

“How does cup-and-ring rock art fit into our overall understanding of the nature of society, beliefs, and external contacts in Argyll and Bute? Currently it tends to be studied in its own right, but it needs to be situated within Late Neolithic practices (and more dating evidence for its creation is needed)”

(Regional Research Framework for Argyll:

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland)

Research Questions

We approached the excavations with a series of broad questions in mind:

Is there a relationship between these carved rocks and the wider landscape, including views, water, and natural features?

Do the carvings interact with the geological features on the rocks, including cracks and fissures?

Is it possible to date the creation or use of these rock art sites?

What is the relationship between the rock art found on bedrock outcrops and that which was built into the fabric of monuments such as standing stones and cists?

Were carved panels made in one visit, or did they accumulate over time?

Can we detect evidence of any activities which took place upon the rocks or around their margins?

What was the environment like when rock art was made?

What was it like to make rock art? What experiences were involved?

Is there a connection between these carved rocks and the sun?

The project investigated three carved outcrops using a combination of survey, excavation and recording. Our specific aims were to:

Record evidence for any features, deposits or artefacts associated with the carvings. Alongside hammerstones and quartz debris, previous projects in the area revealed fragments of flint and Arran pitchstone, as well as evidence of later activities, environmental evidence and dateable materials

Reveal the extent of the carvings. This will allow us to add to the existing records for these sites through survey, photography and photogrammetry (three-dimensional digital recording)

Please click below for further information about the project:

Many thanks

The Carnasserie Farm Rock Art project was funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The fieldwork was co-directed by Dr Aaron Watson and Dr Sharon Webb (Kilmartin Museum) and Dr Gavin MacGregor and Kieran Manchip (Archaeology Scotland). Julia Hamilton and Jacquelyn Condie from Kilmartin Museum’s Education Team facilitated school visits and supported the open days. We want to say a massive thank you to all the volunteers who made the project possible and to geologist Dr Roger Anderton for his expertise. Thanks also to Ann Clark for the lithics analysis, Dr Susan Ramsay for the archaeobotanics and Dr Alison Sheridan for commenting on the pottery. Finally, we extend our grateful thanks to the landowner at Carnasserie Farm, Rosemary Neagle.