Carnasserie Rock Art Excavation 2023

Interpreting the findings

The project has contributed significantly to our understanding of prehistoric rock art in the Kilmartin area and beyond.

All three rock art sites revealed a fascinating story that spans millennia, from geological and glacial processes to post-medieval quarrying. We also revealed fascinating insights into the rock art makers of the Neolithic and Bronze Age.

Rock Art Site 1

At Rock Art Site 1, we uncovered the full extent of the carvings, which are grouped in a distinct cluster. They display a close relationship with natural features on the rock surface and are framed on either side of a natural crack. It may not be a coincidence that Site 1 features the most intricate motifs on the hillside. Views from this panel encompass nearby prehistoric monuments, including massive funerary cairns and standing stones. It also overlooks a junction between routeways at the head of Kilmartin Glen, and is within sight and sound of a waterfall.

We were intrigued by an artificially 'scalloped' edge that had not been created using metal tools. Because of its weathered appearance, geologist Dr Roger Anderton deemed it to be of significant antiquity. This finding is intriguing, as the modification respects and enhances the shape of the carving. To one side of the outcrop, a substantial volume of rock had been removed, but further investigation would be needed to try to determine whether this may have been the source of a cist slab or even a standing stone. A split stone was found in the cavity left behind after the rock was extracted.

Three quartz hammerstones were found, and these were likely used to make the rock art. Of special significance was the discovery of a sherd of decorated pottery, which is a fragment of an early Beaker, dating to between 2500 and 2200 BC. While this doesn’t date the rock art, it is within the timescale of its creation. It is notable that Site 1 is the closest to Upper Largie Quarry, where three comparable early Beakers were discovered in a grave, and are now on display in Kilmartin Museum as part of the Nationally Significant Prehistoric Collection.

Above: The Upper Largie Beakers (KHM KHM 2016.1087, KHM 2016.1089 and KHM 2016.1088).

Rock Art Site 2

The markings at Site 2 appear different in character to those at Site 1, being larger and shallower. They also include some unusual and more amorphous shapes, including oval forms. A trench was dug around the known concentration of cup marks, revealing some important unrecorded carvings: a cup and ring, two partial rings, and a linear groove. Pieces of broken quartz were collected. A single piece of retouched flint was dated to the Later Neolithic.

The freshly exposed surface highlighted how the carvings had been fitted into a preexisting pattern of geological features. An array of linear cracks visually dominates the panel, and these were deliberately carved to align towards the midwinter sunset. There were also smaller weathered pits dotted across the freshly exposed surface. Geologist Roger Anderton suggested that these may have even influenced the placing of the carvings, as many of the cup marks were centred upon these pre-existing eroded hollows.

Above: Geologist Dr Roger Anderton inspecting the markings at Site 2 (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Site 2’s large and shallow markings set it apart from the other panels nearby, but they do have parallels with the broad cups, single rings, and dumbbells found on Bronze Age standing stones and cist slabs in the Kilmartin area.

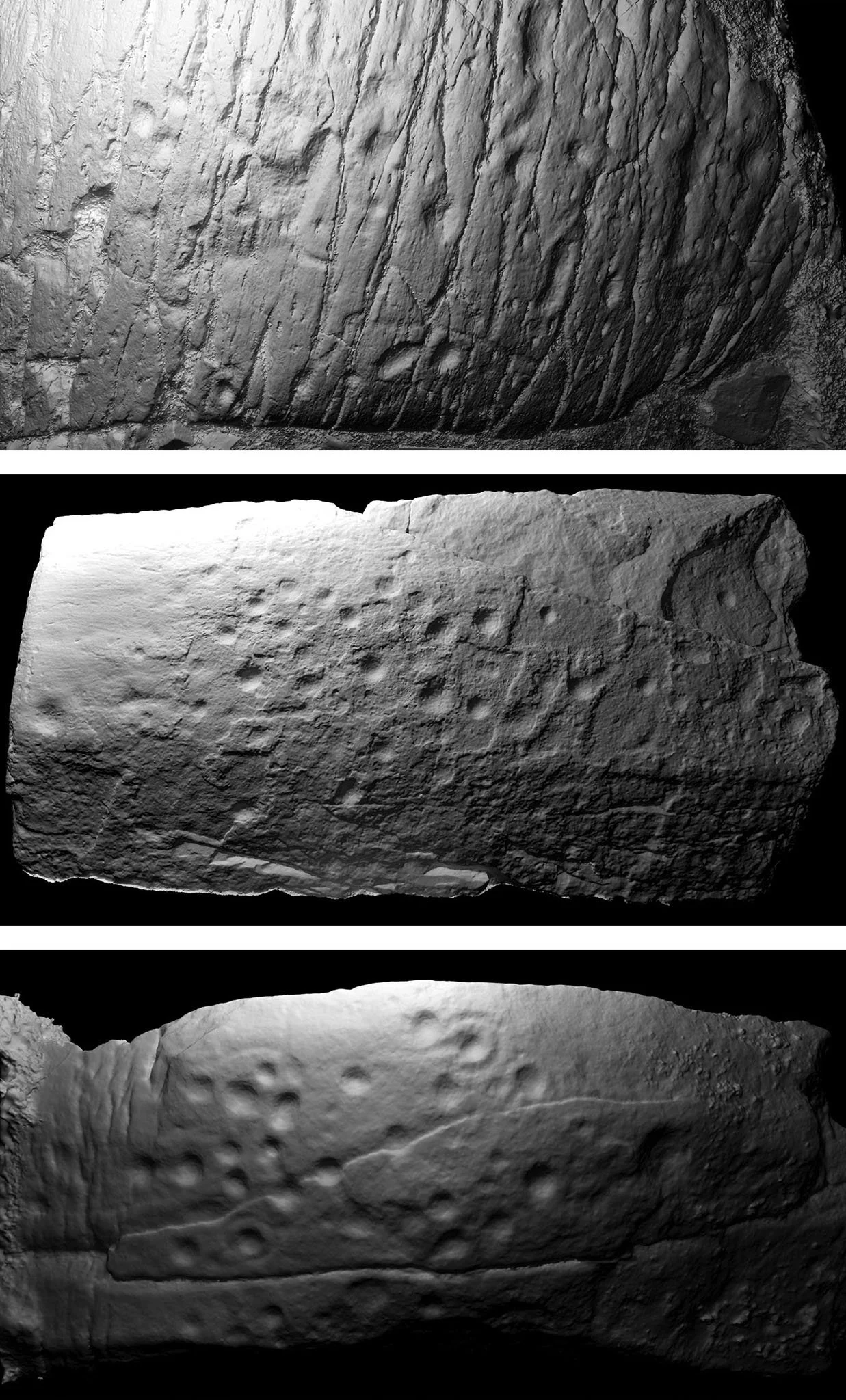

Above: Comparison between Site 2 (upper), Nether Largie North cist slab (middle) and Nether Largie standing stone (lower).

It was noted in the field that two natural hollows combine to create a shape that is reminiscent of a hafted artefact. Close examination revealed that this hollow had also been pecked using a hammerstone. Although tentative, this comparison is intriguing in Kilmartin Glen, the setting for some of the very few monuments in Britain and Ireland where cup marks are found alongside depictions of hafted artefacts. This might lend further credence to a Bronze Age chronology for large dish-like cups at Site 2.

Above: A tentative comparison between a pecked feature at Site 2 and a stylised representation of a hafted artefact.

Rock Art Site 3

Site 3 is a more upstanding outcrop than the others. A sloping panel in a precarious location above a small cliff displays several cup marks, while farther back from the edge are twenty or more closely set cups, one of which has a ring. A trench was opened between the two groups of carvings, but no artefacts or additional carvings were found. This is the location of a hearth, where birch, oak and hazelnut shells were burnt. We don’t have a radiocarbon date for the hearth, but the presence of hazelnut suggests a prehistoric date. Like a comparable hearth at Site 2, we cannoy associate the hearth with the rock art, but it does present an insight into the local environment in prehistory. It also reveals that people were visiting the rocky outcrops at the head of Kilmartin Glen, and it seems very likely that they were known places even before the rock art was added.

A second trench at the foot of the outcrop revealed a layer of closely set stones placed upon bedrock, indicating evidence of medieval or post-medieval quarrying. Beneath these stones, a deep angular crevice displayed the weathered signs of having been shaped in anquity, similar to the outcrop at Site 1.

Above: The deep, triangular shaped crevice, which may have been enhanced in prehistory (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Deep within this fissure were pieces of broken quartz that looked different to any other quartz found so far. They also appeared to be deliberately split, and two of the pieces could be fitted back together. Subsequent analysis confirmed that these fragments were likely parts of a shattered hammerstone, dating back to the time the rock art was created.

Above: Fragments of a hammerstone placed in a deep crevice at Site 3, Trench 6 (Photo: Aaron Watson)

This is reminiscent of intentionally placed deposits, including hammerstones, found at Torbhlaren, as well as further afield at other carved outcrops in Scotland. At Torbhlaren, angular crevices with triangular or diamond shapes are preferred. It may be no coincidence that these forms are shared with the angular carvings found on monuments in Ireland.

Above: Analagous with the broken hammerstone from Carnasserie, this placed deposit is from Torbhlaren. It features two halves of a split quartz flanking a hammerstone, and is now displayed as part of Kilmartin Museum’s Prehistoric Collection (KHM 2021.18, KHM 2021.20 and KHM 2021.19)

Rock art and quartz

The density of worked quartz found at Carnasserie’s rock art sites was modest compared to the assemblages found at Torbhlaren and Ormaig. It was crucial, however, to demonstrate that the rock art at these more modest sites, with fewer and simpler carvings, was also created similarly, using quartz hammerstones. This hints at shared practices between these sites, and similar evidence has emerged in Strath Tay in the Southern Highlands. This use of quartz is distinctive. Its semi-translucent crystals sparkle in the light and, under certain conditions, emit an eerie glow known as triboluminescence.

Relationships with the land and the sun

One of the questions we asked was whether the carvings had a relationship with the sun. At Site 1, the rock surface is angled so the carvings are enhanced by low sun, especially in the wintertime. Indeed, this was how the landowner discovered it. At Site 2, the large cup marks are framed by an array of linear cracks that align toward the winter sunset.

Above: Site 2 being illuminated by low winter sunlight (Photo: Aaron Watson)

The visual references between carvings and the winter sun at Carnasserie reflect wider observations across Kilmartin Glen. Some of the major rock art sites are not only optimally lit in winter sunlight, but were carved upon rocks which fortuitously also align towards the south-west and the midwinter sun. They include Torbhlaren, Cairnbaan and Achnabreck - the largest rock art site in Scotland.

Above: The enormous outcrop at Achnabreck is aligned towards the midwinter sunset (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Site 3 is part of a distinctive rib of rock that extends across the hillside, aligned northeast/southwest, and therefore also marks the winter solstice sunset. The rib displays other discrete clusters of cup marks. A parallel outcrop to the east features a small rock shelter containing a cup and ring. Together, these augmented rock features delineate what could best be described as a routeway, an avenue delineated by outcrops, that is aligned with the winter sun and leads toward a prominent mound on the skyline. Excavations conducted by Kilmartin Museum in 2015 revealed that the summit of this mound, an enhanced natural feature, contained a cist burial. The significance of this feature remains to be tested by future fieldwork.

Above: The location of Site 3 upon a linear outcrop which aligns towards the midsummer sunrise (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Above: Site 3 showing how the skylined cist is framed by outcrops (Photo: Aaron Watson)

Final thoughts

A remarkable quality of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments is not only how they celebrate spectacular connections between people, land, and sky, but also how they continue to inspire and influence us today. Many of the ideas and observations resulting from this project emerged from animated discussions with fieldworkers, many of whom had never practised archaeology before. As they worked in and became familiar with this landscape, they began to see how our experiences in the present can be subtly shaped and influenced by symbols and structures created thousands of years ago.

In turn, we hope that our collective efforts have contributed a new chapter to the evolving story of these fascinating and enigmatic places.

Further information about rock art

Two of Kilmartin Museum’s Evening Talks were dedicated to exploring Kilmartin Glen’s Rock art:

Visit the sites

Kilmartin Museum’s walking guide, In the Footsteps of Kings, includes more information about the context of rock art as well as routes to visit several of the most spectacular sites in the area.

Additional Reading

Bradley, R. 1997. Rock Art and the Prehistory of Atlantic Europe. London: Routledge.

Bradley, R. 2000. The Good Stones: A New Investigation of the Clava Stones. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Jones, A., Freedman, D., O’Connor, B., Lamdin-Whymark, H. (2011) An Animate Landscape: Rock Art and the Prehistory of Kilmartin. Oxford: Windgather Press.

Morris, R. 1977. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Argyll. Dolphin Press.

Morris, R. 1979. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Galloway and the Isle of Man. Poole, Dorset: Blandford Press.

Morris, R. 1981. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Scotland (except Argyll and Galloway). BAR. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Prehistoric Rock Art in Scotland: Archaeology, Meaning and Engagement (ScRAP Booklet, December 2021) - free PDF download

Watson, A. 2022. Experiencing Achnabreck: A Rock Art Site in Kilmartin Glen, Scotland

A free PDF can be downloaded as part of the edited book Abstractions Based on Circles: Papers on prehistoric rock art presented to Stan Beckensall on his 90th birthday, edited by Paul Frodsham and Kate Sharpe.

Please click below for further information about the project:

Many thanks

The Carnasserie Farm Rock Art project was funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The fieldwork was co-directed by Dr Aaron Watson and Dr Sharon Webb (Kilmartin Museum) and Dr Gavin MacGregor and Kieran Manchip (Archaeology Scotland). Julia Hamilton and Jacquelyn Condie from Kilmartin Museum’s Education Team facilitated school visits and supported the open days. We want to say a massive thank you to all the volunteers who made the project possible and to geologist Dr Roger Anderton for his expertise. Thanks also to Ann Clark for the lithics analysis, Dr Susan Ramsay for the archaeobotanics and Dr Alison Sheridan for commenting on the pottery. Finally, we extend our grateful thanks to the landowner at Carnasserie Farm, Rosemary Neagle.